Is this 1984 romance scholarship the root of all the arguments I hate?

In which Janice Radway's Reading the Romance pathologizes a group of romance readers and everyone seems to think she did a good job

Reading the Romance (1984) by Janice Radway is an ethnography of forty-two romance readers from an anonymous town in the Midwest known under the pseudonym, Smithton. Upon its initial release, most literary critics praised Radway’s scholarship (Jane Banks 1986; Patricia Frazer Lamb 1985; Anne Karpf 1985) while later some romance authors took issue with Radway’s characterization of the genre and its readers (Kathleen Gilles Seidel 1992; Laura Kinsale 1992).

In Radway’s 1991 introduction of the second edition, she notes the book has stretched beyond the romance community and contributed to feminist discourse, communication theory, and “the nature of mass consumption” (2). This cross-discipline applicability has led to the book’s popularity and on Google Scholar it shows over 9,000 citations.

Radway intended this book as a starting point for other scholars to measure her ideas and build on. While the books has received criticism, the overall feeling towards Reading the Romance is still one of positivity; that Radway advanced the use of ethnographies in cultural studies and, despite the book’s datedness and limited scope, her work still has relevant insights.

It’s not as if I wish we never speak about Reading the Romance again, quite the opposite. I think its place is pretty firm in romance scholarship, yet I disagree with how scholars still cite some of Radway’s conclusions as profound. There is a fatal flaw to this work in Radway’s use of psychoanalytical theory as applied to this ethnography, or at least how Radway interprets and uses psychoanalysis on the Smithton readers.

The feminist-psychoanalysis she relies on comes from sociologist Nancy Chodorow’s seminal work The Reproduction of Mothering (1978). Chodorow’s thesis is that the caregiving division of labor in the patriarchal family leads to separate personality development for men and women who replicate that caregiving model. Chodorow uses object-relations theory to describe how children’s relationship with their mother in their earliest years results in internalizing this labor model. The “affective tone” (135) and mother-infant relationship affect how children relate to people later in life.

Because this is psychoanalysis, Chodorow talks about a girl’s pre-oedipal and oedipal period. We don’t need to dive too deeply into this, but the gist is, a girl maintains “an intense emotional commitment to her mother and all that is female” resulting in a woman who “wishes to regress into infancy to reconstruct the lost intensity of the mother-daughter bond” (136).

Now, I wouldn’t have so much an issue with this if Radway did a Freudian reading of several romance novels and that was her book. We have ideas in society that inform art and so going back and reading texts with those theories in mind is fruitful. Phrenology is a debunked theory, but reading Edgar Allan Poe’s work with a phrenology lens would yield interesting scholarship. To my despair, Radway analyzes the Smithton readers instead of romance texts.

One criticism pretty much everyone agrees on is the limited sample size. Honestly though, I don’t think the small sample size is bad because this is a qualitative study. The strength of qualitative studies is they’re a deep dive into a few cases to find questions you didn’t think to ask. That kind of information might yield brand new data points. Not all data is quantifiable, so a qualitative study can account for that.

The most damning thing about this book is that Radway doesn’t let the Smithton readers speak for themselves. Sure, she quotes them. She has tables and results from some of her questionnaires based on what they said. She talks about interactions. This book, though, is primarily her analysis and Radway speaks for and over the Smithton women. I don’t want to come out and say there’s a low murmur of condescension throughout this book because Radway in text criticizes other critics for that, but there is. She’s a scholar; these are housewives. (Mostly.) They don’t “consciously” make certain connections because, well, did I mention they’re only housewives?

Helen Sterk has an observation in her 1986 review that validated my feelings about Radway’s approach to the Smithton readers:

She commits the same mistake with her group of readers that she claims critics do with romances. Several brief pages after Radway disparages critics for imposing their sophisticated reading on a naïve text, she rationalizes her own essentializing interpretation of her reader’s “folk” accounts of their reading, by pointing out that her women readers neither consciously know nor realize their patriarchal conditioning. Since they do not know their own blindness, according to Radway, they cannot see in themselves what she, the impartial, educated observer can see. If Radway had allowed her respondents their own voices rather than channeling them through hers, she would have enhanced the value and credibility of her study. (349)

Let’s get into it.

The 1991 preface

Radway has several important realizations in her 1991 preface of Reading the Romance that I want to frame my discussion with. She emphasizes how her book captured a particular moment in time, which was informed by her growing feminism and political interest in Marxism.

In 1977, Radway was hired by the American Civilization Department at the University of Pennsylvania. The American Civilization Department pushed back against what Radway called the “hegemony of New Criticism in English literary departments” (2). New Criticism interrogates the text only, excluding history or things in the author’s biography that might influence a text. The American Civilization Department formed across disciplines and was built on the idea that America’s most reliable history was its art. Radway’s colleagues argued that a more reliable history would be found in popular literature since it reflected the taste of ordinary Americans and that should be the focus of studying culture. She says she got hired because of her background in popular literature.

The American Civilization Department shifted from a “literary-moral” (3) definition of culture to an anthropological one. The department required graduate seminars to be structured as ethnographies of particular communities. At the same time The Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham turned to ethnographies to study the necessary struggle between subgroups or “different ways of life” (4). A divide between American and English traditions came about because scholars in America in their early work didn’t hold to the Marxist tradition the way the English did.

How this loose Marxist tradition crops up in Reading the Romance is Radway’s chapter on the history of publishing. Helen Sterk notes how this chapter seems disconnected from the rest of the book. I agree with that because it seems to me Radway never connects the dots about Marxism and mass-market books. She won’t come out and say the Marxist thing, that mass market novels are the opiate for the masses, rather the chapter implies it.

Back to the preface, in response to her colleagues’ inquiries about “the theoretical work on the reader developing within the literary critical community and semiotic conceptions of the literary text” (4) and “what a literary text could be taken as evidence for,” (2) Radway turned to ethnographies to discover how groups or communities of readers read texts.

Her initial approach aimed at replacing textual interpretation with the more “empirical” ethnography, since it would more accurately describe a text’s relationship to its audience. She brings up the debate within the American Studies community of “scientific” versus “‘literary’ methods in cultural study” (5). This makes sense when you consider the American Civilization Department pushed back so strongly against New Criticism.

In hindsight, Radway realized ethnographies couldn’t be purely empirical since her views of the Smithton women would be an interpretation of an interpretation and “that even what I took to be simple descriptions of my interviewees’ self-understandings were mediated if not produced by my own conceptual constructs of ways of seeing the world” (5). So, her interpretation would run through her ideological lens.

If writing Reading the Romance today Radway suggests several changes she would make to her own work:

1. Make the difference clearer between her observations and the comments by the Smithton women.

2. Include more from her interviews and transcripts and detail the changing relationships between her and the Smithton women.

3. No longer argue to have ethnographies replace textual analysis and that it should be one tool of several that scholars use.

4. Disclose her ideological position so the reader knows how she produces her lens of interpretation. Radway cites neo-Marxism and feminism as her lens.

At least the 1991 version of Radway agrees with me about adding in more of the interviews from the Smithton readers. This brings me to another point about how she chose this group of readers.

Sometimes Radway frames the homogeneity of the Smithton women with trepidation, like she sees the idea still has merit despite this homogeneity, but the similarities of their positions as wives and mothers seem to be part of the inspiration for this book:

Indeed, it was the women readers’ construction of the act of romance reading as a “declaration of independence” that surprised me into the realization that the meaning of their media use was multiply determined and internally contradictory and that to get at its complexity, it would be helpful to distinguish analytically between the significance of the event of reading and the meaning of the text constructed as its consequence…What the book gradually became, then, was less an account of the way romances as texts were interpreted than of the way romance reading as a form of behavior operated as a complex intervention in the ongoing social life of actual social subjects, women who saw themselves first as wives and mothers. (7)

Connecting this loose collection of customers to their status as wives and mothers becomes foundational to Reading the Romance. Radway argues these women found as repeat customers at a chain bookstore could be a kind of subgroup, even despite her earlier qualms about how Reading the Romance fails to define membership in the romance community. Instead, she focuses on the more solid identity of marriage and family since about seventy-six percent of the Smithton readers were married and seventy percent had kids.

I must point out two things. First, there were single, divorced, and widowed readers within the group. Second, at one point a book seller reveals some male customers who said they were buying romance novels for their wives, although she suspected they bought for themselves (55). At least within the Smithton homogeneity, there are deviations that Radway didn’t really focus on besides as a cursory acknowledgement before moving on.

But why the romance genre? Radway explains she was interested in feminist scholarly writing and saw “the study of romance as a way to engage with this literature” (6). I will come down hard on Radway in the rest of this essay, but I will say this: it’s jarring to read contemporary reviews and scholarship of Reading the Romance because it seems like such a give in that romance is moving women’s liberation backwards. While I hate the swing the other way, romance is inherently feminist, I think it’s important to note these general assumptions.

More on genre here. Radway compares her book to another, The Nationwide Audience by David Morley who argued turning to a genre-based theory of interpretation and interaction would result in better audience research:

A theory in which genre is conceived as a set of rules for the production of meaning, operable both through writing and reading, might be able to explain why certain sets of texts are especially interesting to particular groups of people (and not to others) because it would direct one’s attention to the question of how and where a given set of generic rules had been created, learned and used. (10)

It’s not an incredible or outlandish question to ask: why do certain people prefer one genre over the other? How do genre writers conceive of meaning versus readers? These sorts of ground zero questions could be the basis of some kind of scholarship.

Radway adds that although she didn’t use those terms, she creates a similar theory about genre:

To begin with, [Reading the Romance] attempts to understand how the Smithton women’s social and material situation prepares them to find the act of reading attractive and even necessary. Secondly, through detailed questioning of the women about their own definition of romance and their criteria for distinguishing between ideal and failed versions of the genre, the study attempts to characterize the structure of the particular narrative the women have chosen to engage because they find it especially enjoyable. Finally, through its use of psychoanalytic theory, the book attempts to explain how and why such a structured “story” might be experienced as pleasurable by those women as a consequence of their socialization within a particular family unit. (10-11)

This quote cements how she ties genre, reading, sociology, and psychoanalytic theory all together. This attempt to explain how readers define “successful” or “failed” romances I think could’ve been more fruitful of a book if Radway had done as she wished she had: interviewed the Smithton readers and included their responses more thoroughly into her book. And yet, it’s that final inclusion of psychoanalytic theory I think that dooms this whole enterprise. I can’t tell if I’m uncharitable in characterizing Reading the Romance as being no better than your run-of-the-mill think piece that pathologizes romance readers, but honestly, I’m not sure if it is.

The scholar vs. the housewives

Radway contrasts New York City’s gleaming towers with Smithton’s cornfields where women with master’s degrees in literature compile books consumed by women “devoted almost wholly to the care of others” (46).

She contacted Dorothy Evans because Dorothy wrote a review newsletter and developed “a national reputation” to the point editors sent her galley proofs. Radway wrote to her in December 1979 asking what her criteria was and if she’d be open to chat. Dorothy agreed and facilitated meetings for Radway with some of her customers at the chain bookstore she worked at.

Initially, Radway interviewed sixteen readers as a group in two, four-hour open-ended discussions. Then she met with five readers individually. Then she met five formal times with Dorothy, although Radway and Dorothy had several informal discussions as well. Her first questionnaire went to sixteen readers.

She arrived home after this initial visit, where she tried to read as many of the titles mentioned as she could, transcribed the taped interviews, and added notes in her field-work journal. She redesigned a questionnaire based on this first pass of conversations and mailed Dorothy fifty copies and asked to give them to her recurring customers. Dorothy sent forty-two in return.

Radway issues a caution in chapter two about the sameness of the romance readers she interviews. She acknowledges the limited nature of the group meant it shouldn’t be taken as a “scientifically designed random sample,” (48) therefore conclusions about romance readers should be drawn cautiously and not applied broadly. She reiterates that her study’s “propositions ought to be considered hypotheses that now must be tested systematically by looking at a much broader and unrelated group of romance readers” (49). Here she states moving ahead for two reasons: First, Dorothy’s national reputation with the romance genre, and second, her recurring customers were a stable group.

On the surface I could see how Radway comes across as supportive of reading romance, almost making it into this feminist act.

I try to make a case for seeing romance reading as a form of individual resistance to a situation predicated on the assumption that it is women alone who are responsible for the care and emotional nurture of others. Romance reading buys time and privacy for women even as it addresses the corollary consequence of their situation, the physical exhaustion and emotional depletion brought about by the fact that no one within the patriarchal family is charged with their care. Given the Smithton women’s highly specific references to such costs, I found it impossible to ignore their equally fervent insistence that romance reading creates a feeling of hope, provides emotional sustenance, and produces a fully visceral sense of well-being. (12)

I could pull quotes similar to this one, mostly from the start of the book, and make a pretty good case that Radway supports romance and romance readers when it’s not exactly like that. Radway is remarkably incurious about why reading is the hobby of choice or if they had other hobbies. She doesn’t make the connection that I think she should about the restorative power of hobbies and by extension reading romance novels. Reading any book of any genre would be considered a hobby or time reclamation. She needs to make this argument genre specific for why romance novels particularly meets this need, which she eventually does by arguing that readers indulge in a fantasy where heroes nurture the heroines and readers derive emotional sustenance from that.

Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?

I’m honestly a little floored by the condescension in this book. Perhaps it flies under the radar when it’s draped in scholar-speak. Take this, for example:

Moreover, because the Smithton women feel an admittedly intense need to indulge in the romantic fantasy and, for the most part, cannot fulfill that need with their own imaginative activity, they often buy books they do not really like or fully endorse. As one reader explained, “Sometimes even a bad book is better than nothing.” (50, emphasis my own)

What a bad faith read of what that person said.

Radway really leans into this reading as a fantasy escape argument. In chapter two, “The Readers and Their Romances,” Radway compares the reading habits of the Smithton women to other romance readers. She suggests their excessive romance reading fills a “deep psychological need” and I think it’s telling that she says the Smithton women read “religiously” (59) every day.

To be kind of fair to Radway, she picked the word “escape” after the Smithton readers used it in prior conversations with her, although she really ran with it. In the table below, Radway asked the readers to rank the three most important factors in why they read romance.

As you might notice, answers “c” and “e” are the highest and the actual answers with the word escape in them don’t score as high. Radway had an explanation for this. In a group interview, “two unusually articulate readers” (61) explained that “escape” is more synonymous with “relaxation,” which prompted Radway to put these terms on her questionnaire. Before Radway introduces the above responses, she frames it by saying this:

Rather, Dot’s customers are women who spend a significant portion of every day participating vicariously in a fantasy world that they willingly admit bears little resemblance to the one they actually inhabit. Clearly, the experience must provide some form of required pleasure and reconstitution because it seems unlikely that so much time and money would be spent on an activity that functioned merely to fill otherwise unoccupied time. (60)

Radway adds a psychological weight to the words “escape” and “fantasy” that don’t reflect how these readers see their own activity. Like CLEARLY it has to be something more than a hobby, pastime, or favorite activity. I find Radway so dismissive that I wonder if the psychoanalysis lens doomed her results from the start. The focus on the unconscious often motivated Radway to disregard what the readers actually said in search of a supposed deeper meaning.

A lot of condescension comes through references to how the Smithton women consciously or unconsciously absorb messaging from the romance novels they read. Like Helen Sterk said in her review, apparently they don’t know their own condition and they don’t have sophisticated literary skills. Like, Radway says this at some point when referencing a scene from a Johanna Lindsey novel, “Although I doubt very much that the Smithton readers know how to read this psychoanalytically as a symbol of a desire” (125). While I’ve already complained about Radway talking over her readers, it’s most notable in this section where Radway discusses and categorizes the romance novels she reads, rather than more thoroughly discussing and documenting her readers’ responses to romance novels.

In chapter three “The Act of Reading the Romance: Escape and Instruction,” Radway discusses how the Smithton readers like learning facts about history from historical romance. Some even share what they learn with their family members. She takes this and warps it into handwringing over the messages readers are unconsciously taking in. Like much of the book, Radway starts by assigning some agency to the reader and then resorts to the, they don’t know they’re controlled by the patriarchy, argument.

It would be easy enough to dismiss the Smithton readers’ conflicting beliefs about the realism of the romantic fantasy by attributing them to a lack of literary sophistication. Such a move, however, would once again deny the worth of the readers’ understanding of their own experience and thus ignore a very useful form of evidence in the effort to reconstruct the complexity of their use of romantic fiction. It seems advisable, then, to treat their contradictory beliefs as evidence, at least, of an ambivalent attitude toward the reality of the story. The women may in fact believe the stories are only fantasies on one level at the very same time that they take other aspects of them to be real and therefore apply information learned about the fictional world to the events and occurrences of theirs. If they do so utilize some fictional propositions, it may well be the case that the readers also unconsciously take others having to do with the nature of the heroine’s fate as generally applicable to the lives of real women. In that case, no matter what the women intend their act of reading to say about their roles as wives and mothers, the ideological force of the reading experience could, finally, be a conservative one. In reading about a woman who manages to find her identity through the care of a nurturant protector and sexual partner, the Smithton readers might well be teaching themselves to believe in the worth of such a route to fulfillment and encouraging the hope that such a route might yet open up for them as it once did for the heroine. (186-187)

She reiterates how the Smithton readers absorb a conservative ideology on the following page.

And yet, the group’s equally insistent emphasis on the romance’s capacity to instruct them about history and geography suggests that they also believe that the universe of the romantic fantasy is somehow congruent, if not continuous, with the one they inhabit. One has to wonder, then, how much of the romance’s conservative ideology about the nature of womanhood is inadvertently “learned” during the reading process and generalized as normal, natural, female development in the real world. (188)

I originally said I find Radway infuses low-level condescension into Reading the Romance but as I’ve re-read and pulled more quotes, it feels like this book is dripping with condescension.

The conservative ideology thing. It’s a lot. I’m not arguing that romances or stories can’t have conservative themes or ideologies, because like any genre, there are tons of romance stories that do. But Radway makes it seem like the inherent presence of marriage to a man or children means the novel is conservative.

Okay, let’s talk about how Radway discusses romance novels and what message the romance reader absorbs.

What does she say about romance texts?

Radway looks to Dorothy and her readers to define a “successful” romantic text. From chapter one where Radway lays out her excellent history of mass market publishing, she makes an observation I agree with, that there can be a disconnect between what the reader wants and what a publisher publishes. Because of this, she seems keen to have the Smithton readers define what’s “good” and what’s “bad” in a romance.

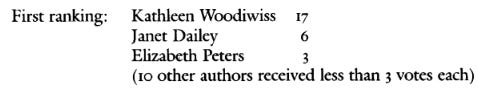

In chapter four, with the throw-up inducing title “The Ideal Romance: The Promise of Patriarchy,” Radway asks the Smithton readers for their three favorite authors and their three favorite romance novels. Here are the results:

BOOKS

AUTHORS

She read some of these titles and then some of the “five-star” reads recommended by Dorothy.

Radway’s next group of observations notes how the heroine in these books often rejects femininity or femaleness initially and the common occurrence of the “spirited heroine.” There’s this: “Several writers establish their heroine’s refusal to be restricted by expectations about female gender behavior by assigning them unusual jobs,” (124) which my friend Emma has an excellent article about hot girl hobbies. In Johanna Lindsey’s Fires of Winter, the heroine eschews needlework and hides her hair. The Flame and the Flower has a character marked by education that separates her from the other female characters. Radway fits these observations into Chodorow’s psychoanalytical profile, arguing these “ambivalent feelings” (123) about being female is the first step for the heroine and reader’s journey towards autonomy. Once the heroine achieves this individuation then she can have a mother-like relationship with the male hero who cares for her. This relates to David Morley’s theory of genre, where this dynamic draws certain kinds of readers to this particular genre.

Romance novels, though, aren’t about mothers and daughters, at least not on the surface. What Radway identifies after reading several romances and hearing about the care loads these women have is that women want a relationship where they can be cared for. Radway apparently doesn’t see any of these fictional relationships as reciprocal, rather, it’s all about the heroine, and by extension, the supposed female reader who projects herself into the heroine.

This sort of argument leads us down the road of what women learn from romance and how it teaches women to date insensitive men.

The romance inadvertently tells its readers, then, that she will receive the kind of care she desires only if she can find a man who is already tender and nurturant. This hole in the romance’s explanatory logic is precisely the point at which a potential argument for change is transformed into a representation and recommendation of the status quo. The reader is not shown how to find a nurturant man nor how to hold a distant one responsible for altering his lack of emotional availability. Neither is she encouraged to believe that male indifference and independence can really be altered. What she is encouraged to do is to latch on to whatever expressions of thoughtfulness he might display, no matter how few, and to consider them, rather than his more obvious and frequent disinterest, as evidence of his true character. (149)

It’s beyond me why Radway doesn’t clock this as necessary conflict to a book. Characters are indifferent to each other until they aren’t. Sometimes a character treats another character badly before the romance progresses. Romance is a character-driven genre, so characters drive the conflict. There would be no story without these conflicts.

I’m not sure why I said it was beyond me because I understand Radway is making a romance-novels-are-instruction argument. Therefore, the bad ways characters treat each other means the passive reader learns all the wrong things about relationships.

Equally significant, however, the romance also provides a symbolic portrait of the womanly sensibility that is created and required by patriarchal marriage and its sexual division of labor. By showing that the heroine finds someone who is intensely and exclusively interested in her and in her needs, the romance confirms the validity of the reader’s desire for tender nurture, legitimizes her pre-oedipal wish to recover the primary love of her initial caretaker. Simultaneously, by witnessing her connection with an autonomous and powerful male, it also confirms her longing to be protected, provided for, and sexually desired. The romance legitimizes her own heterosexuality and decision to marry by providing the heroine with a spectacularly masculine partner and a perfect marriage. In thus symbolically reproducing the triangular object configuration that characterizes female personality development through the heroine’s relationships, the romance underscores and shores up the very psychological structure that guarantees women’s continuing commitment to marriage and motherhood. It manages to do so, finally, because it also includes a set of very usable instructions that she will not reject her current partner or hold out for the precise combination of tenderness and power that the heroine discovers in the hero. Because romance provides its reader with the strategy and ability to reinterpret her own relationship, it insures patriarchal culture against the possibility that she might demand to have both her need for nurturance and adult heterosexual love met by a single individual. (150-151)

This is a pretty strong indictment of a hobby. Imagine you like reading romance books, but actually you’re holding up the patriarchy and re-contextualizing your obviously bad relationship into a good one. What’s especially annoying is that there is a fair critique buried in there. On the genre level, yes, there are a lot of heterosexual couples who get married at the end of a romance novel. That’s a fair one. If romance explores romantic love, then it should be romantic love in all its forms; however, Radway doesn’t interrogate publishing’s role in this, rather lays the blame at the feet of the individual reader who keeps falling victim to patriarchal marriage.

Conclusion: romances are inherently feminist is the same argument

When a reader picks up a romance novel, what ideology do they absorb? Radway says women learn to stay trapped in their patriarchal marriages with their uneven domestic load. The new argument is that romance novels are feminist actually. While completely unpacking that argument might be another essay, it’s the same argument in that it argues romance novels are instruction novels except now the instruction means readers learn about consent I guess. Both these groups believe romance is or should be teaching something. Romance is either romanticizing abuse or empowering readers through it’s portrayal of healthy relationships.

My new best friends, sociologists Marcella Thompson, Patricia Koski, and Lori Holyfield, in their 1997 article “Romance and agency” show how Radway treats romance readers as an “untapped army” that needs to be shown the feminist way. They evaluate her stance as an academic and issue a caution to other scholars to not superimpose their ideology on their subjects.

They argue that Radway’s argument devolves into the familiar claim that women use romance novels to escape only with a veneer of empowerment over it. Radway creates an “us versus them” reality where feminists must inform the un-feminist reader that the patriarchy guides their decisions and their true agency comes in “how to respond to their powerless condition…This view has simply reinforced the hegemonic determinism that feminist critics have so adamantly opposed” (447).

Thompson and company’s article articulated the shortfalls of Radway so well, I was tempted to re-print it here in its entirety, instead I will lean on them for one last point: how should a sociologist/academic view the subjects of their research?

A true agency argument is a tricky position for the sociologist. How can sociologists view the subjects of their research as self-determining while also believing that their research has something to offer in terms of enlightenment? Many feminists have argued that the view of the sociologist cannot be privileged over that of the participants—that people’s views of their lives must be seen as genuine. Thus, the roles of academics must be held in check…Feminist researchers have warned against the research that imposes a feminist understanding as opposed to one that draws on such an understanding to interpret women’s experiences from their own standpoints. It is counterproductive to assume that readers of romance do not posses a framework that at once allows them to combine an objective understanding of their position in relation to men with a subjective acknowledgement of their practice of reading. Clearly, if sociologists claim to have an agency argument, what they cannot do is assume that people are acting out of a false consciousness created by a hegemonic structure, whether that be the patriarchy, capitalism, or anything else. With regard to the romance novel, a real agency argument must give women (and men) the true power of self-creation and self-determination. This is not to deny the social context, only remind researchers of their omniscient tendencies. Women may read romance for compensatory reasons, to empower, or for sheer relaxation. They may write romances for creativity, income, or a multitude of reasons anyone chooses to write. It must be their interpretation, their choice. Of course, writers and readers cannot control all of the conditions of the text. Nonetheless, sociologists cannot say that the reasons women give for reading romances are really a defense mechanism against ‘persistent and nagging feels of inadequacy and lack of self-worth which are themselves the product of consistent subordination and domination’ (Radway 1984:26). If they do this, they are simply making women pawns in their political game—a hegemony no less controlling than patriarchy itself. (447-448)

So, to answer the question of my title yes and no. I don’t think Radway is the source of these bad arguments; however, she laundered them through academia, giving them some amount of credibility. Her status as an academic means I still see citations to her positively. Like on Reddit. Like in this romance think piece. Now, you might want to argue with me that Radway used the “correct” view. She’s a feminist! She feministly spoke over a group of female romance readers and told the rest of us their hobby is fantasy-escapism that’s damaging to women.

I want to move conversation about the romance genre into a more neutral place. It is a genre just like horror, mystery, sci-fi, and fantasy. Viewing romance this way allows for it to be more. Be daring and controversial. To have characters do terrible things without the weight that somehow this is teaching the reader that they should accept maltreatment. I’m talking like romance isn’t like this already. There are so many romance novels that have characters doing terrible things to each other, and that’s great; however, the lens in reviewing these novels needs to change. The conflicts in romance shouldn’t be seen as inherently anti-feminist or teaching the reader the wrong thing rather its a genre interested in all kinds of conflicts between characters. Personally, it’s why I like romance and I hate that Radway’s argument still shows up in reviews and think pieces.

Beth!! This is such a great read! A very well constructed argument that is also hilarious. I too hope that discussions of romance novels are headed towards a more neutral place on the whole.

This was such a fun (and shocking) read, Beth! Down with reductive romance takes!!!